The power of a black screen: a game changer for civic learning?

5 min read

Social media and pop culture have changed the way young people engage with the world, but what about the way we teach civic engagement? Michael Noonan unpacks ISV’s latest research on the link between civic engagement and arts education.

During the first COVID-19 lockdown, I heard on the grapevine that some famous guitarists, relieved of touring schedules and studio work thanks to global pandemic, were providing free Instagram lessons.

I signed up, logged on and…. all I saw were black screens. Deliberate blank posts from artists across the world expressing support for the most recent #BlackLivesMatter protests in the United States.

Artists have always asked difficult questions of society and forced reflection on civic issues. Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 painting, The Death of Marat, depicting a murdered journalist during the French Revolution is just one famous example.

In the past, such artworks often hung in galleries accessible to a scant few; today art that reflects on civic issues crosses borders and cultures at breakneck speed.

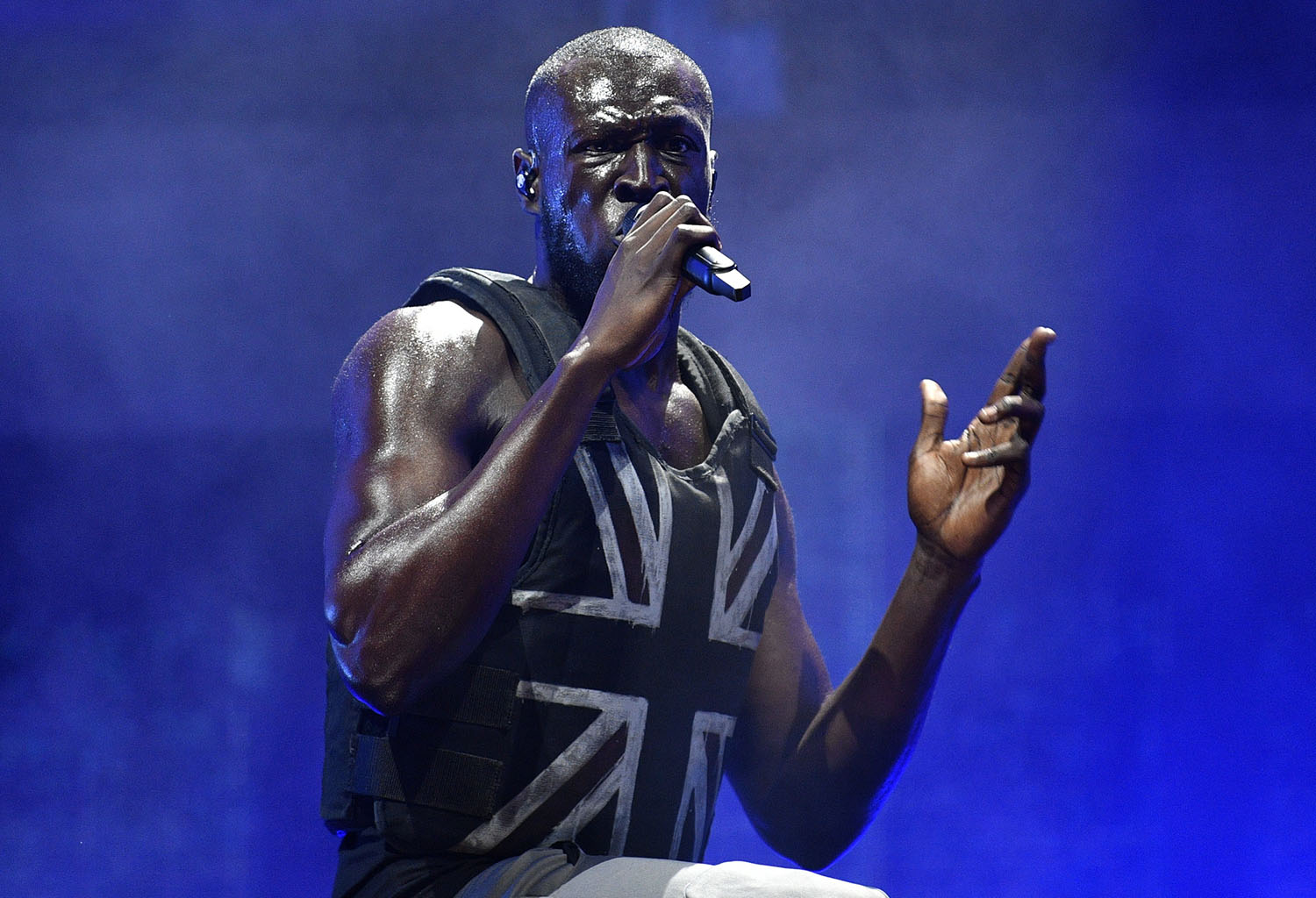

And what constitutes art has changed as well. At last year’s Glastonbury Festival, UK grime artist Stormzy performed the headline set in a Union Jack stab vest designed by renowned street artist Banksy. The artwork represented Brexit’s fracturing of the United Kingdom,

Britain’s knife crime crisis and racial inequality. Unlike The Death of Marat, Banksy’s piece and its cultural and political significance was seen by 200,000 festival goers within minutes – and by millions on Instagram within hours.

“In making or responding to art and engaging with civic issues, humans seek basically the same outcome: to develop common values and shared meaning.”

Stormzy modelling Banksy’s Union Jack Stab Vest at Glastonbury in 2019.

Image © Neil Hall/EPA.

The link between the arts and civic engagement

For the past two years, Independent Schools Victoria’s research team has worked with Harvard University’s Project Zero to explore the link between arts and civic engagement and how arts education can expand civic learning opportunities in schools.

Through our research we found numerous studies across the world that proved there is a strong correlation between engaging with, or creating, art and increased civic engagement.

This is unsurprising, really. In making or responding to art and engaging with civic issues, humans seek basically the same outcome: to develop common values and shared meaning.

Twenty-first century examples of civic engagement and discourse like Banksy’s stab vest should not be taken lightly. Smartphones in the hand of billions connects us like never before. And it’s here – on social media and through absorbing popular culture – that our youth engage with ideas that will help shape their purpose, values and beliefs.

But this sociocultural framework underpinning how young people engage with issues of civic importance is at odds with what we teach in schools. Our research found that most schools follow a predominately institutional view of civic engagement, which is typically based on understanding democracy, parliament and the rule of law.

This intuitional approach to teaching civics and citizenship is very important. However, to ensure students become active global citizens equipped with the skills to engage with global challenges, we must also interrogate how we teach civic engagement from a sociocultural standpoint.

“The spread of conspiracy theories based on fake news and flawed logic during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic provides a clear example of why we need to teach our youth to engage thoughtfully and flexibly with issues of civic importance.”

Bridging the gap for authentic civic engagement

Can involving the arts bridge this gap and provide students with more personal, meaningful and authentic civic learning opportunities at school?

This is an important question. As we careen further into the twenty-first century, the world is becoming a smaller, more connected place. Issues of civic importance are no longer only local or national. And as the reaction to the death of George Floyd demonstrates, they are often global.

But the increased speed with which people engage and coalesce around issues of civic discourse through social media can have an unpleasant side. The spread of conspiracy theories based on fake news and flawed logic during the current COVID-19 pandemic provides a clear example of why we need to teach our youth to engage thoughtfully and flexibly with issues of civic importance.

Our research set out to investigate what role arts education currently plays in Victorian Independent schools in providing teachers with the sociocultural framework to create civic learning opportunities for students. Alongside an extensive literature review we surveyed school leaders and arts and humanities teachers and conducted follow-up interviews with select participants.

Despite the clear benefits associated with involving the arts in creating civic learning opportunities, the study found that – in participating schools – this occurs in pockets and is typically unstructured and ad hoc.

Around half of respondents agreed that civic engagement is a process of cultural and artistic exchange, yet they generally perceived art-related civic learning experiences as less important for students than non-art civic learning experiences. Arts teachers or respondents at schools invested in the arts were more likely to see the importance of art-related civic learning experiences, as were respondents from schools serving families from high socio-economic backgrounds.

The benefits of cross-collaboration

This suggests that the benefits of linking the arts and civic learning is not widely understood. Our partners at Project Zero are currently working on a suite of tools and frameworks to help educators better understand the benefits of cross-collaboration with the arts and civic learning.

The research findings also suggest there is a need for curriculum bodies to highlight the role of the arts in engaging students in civic discourse and to provide more guidance for educators teaching civics and citizenship on how to include the arts in this pursuit.

We feel there is a lot at stake here.

If students are to take advantage of the opportunities of the fourth industrial revolution, they will need to think and act as global citizens to resolve problems long emancipated from national borders. But measures and metrics of civic engagement levels of young people are declining.

What’s required is a new approach to teaching students to understand their role as global citizens through more modern, twenty-first century notions of what it means to be civically engaged.

As we confront the challenges of the new century, we need less conspiracy theorists lacking the skills to engage with civic issues in a balanced, reflective way. Involving the arts can create structured processes for students to participate in civic society that will help harness and grow the balanced and reflective expressions of civic values we will require.

The kind of thoughtful, subtle expressions of civic values so elegantly (and controversially) expressed through a black Instagram post.

Michael Noonan was Head of Research and Technology at Independent Schools Victoria.