Doing the right thing for students with disability

4 min read

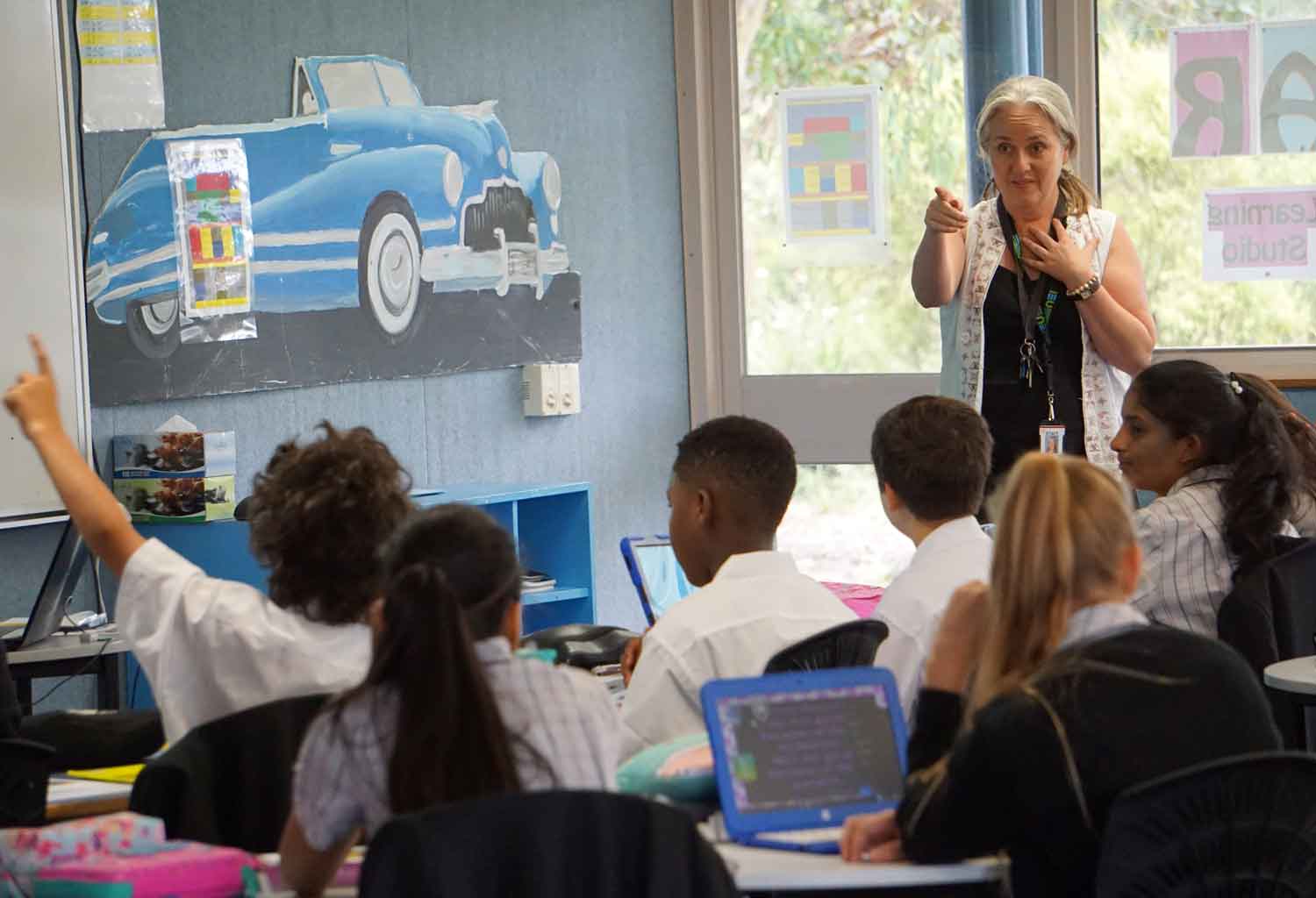

For the past three years, teachers in all schools in all states have been collecting data in an attempt to do the right thing: to identify, record and meet the needs of students with disability.

It’s a massive undertaking, given that across the country there are close to 3.8 million students attending more than 9000 schools that employ more than 270,000 teachers.

It’s complicated by Australia’s federal structure, with students enrolled in government schools in eight states and territories, and in Independent and Catholic schools.

There are further layers of complexity, involving individual teachers in individual schools assessing whether a student has a disability, assessing the nature and level of that disability, and deciding whether the disability requires teachers to make ‘adjustments’ to ensure students are not disadvantaged in their education. It’s about ensuring students’ rights are met.

If teachers, applying their professional judgement, decide they do need to make adjustments, they then have to decide the level of adjustment – whether they can meet the needs of students by adapting their normal teaching practices, or whether the students need additional support. If they do need that support, then teachers have to decide at what level – supplementary, substantial or extensive.

This process is called the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data for Students with Disability (NCCD). It’s supported by all levels of government and all school sectors, and based on legislation and regulation that mean that schools are legally obliged to meet student needs.

Another level of complexity was added this year when, under the Australian Government’s Gonski 2.0 education reforms, government funding for students with disability was tied to the NCCD.

This change addresses the weaknesses of the previous system, which imposed onerous clinical assessments on students and narrowly defined disability in a way that underestimated the number who might need additional support.

The new system, based on definitions of disability in the Disability Discrimination Act, is much broader. And it draws on the practical day-to-day and face-to-face experience of classroom teachers who are better able to identify students who need support.

As a result, it’s no surprise that schools are reporting higher numbers under the NCCD.

As noted, up until this year there was no link between the NCCD and Australian Government funding. But not all students judged to have a disability are eligible for support that involves additional funding – those with asthma or allergies, for example.

Since it’s a new system, and while external consultants have declared the data collected so far is robust, some of the imperfections, variations and inconsistencies take time to become apparent and can be rectified.

Some of the variations in assessments between schools and states depend on the experience and understanding of the new model of the teachers involved.

The Australian Government recognises that this is a massive undertaking and is spending $20 million to ensure the quality of the data. People involved in education, include ISV staff, recognise that some teachers might need additional training, professional learning and more information on the NCCD model so that it is consistently applied.

For its part, ISV is committed to ensuring the system is based on quality data.

Our staff have undertaken data moderation with Member Schools and with schools in other sectors. We have explained to Member Schools the nationally consistent guidelines. And, in our engagement with departmental officials and school sector representatives, we have continually stressed the need for greater quality assurance and moderation of data in all school sectors.

As I said, this is a massive and complicated undertaking – but it’s one that’s worth doing and one we’re committed to improving.

Michelle Green was Chief Executive of Independent Schools Victoria from 2002–2023.